12:30 PM | *2017 is ending as a down year in global tropical activity*

Paul Dorian

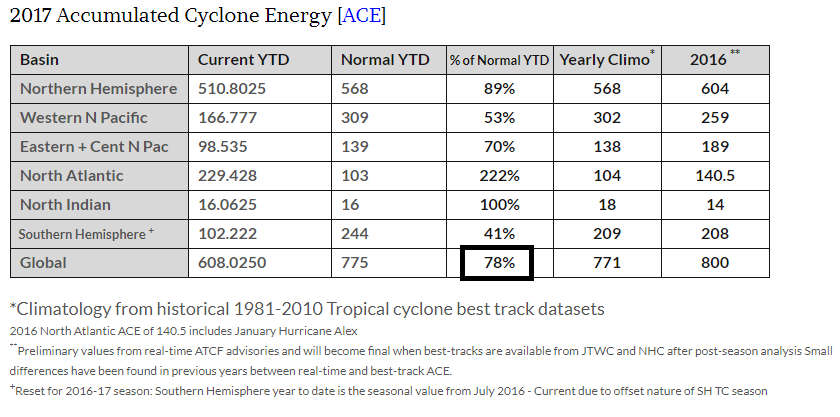

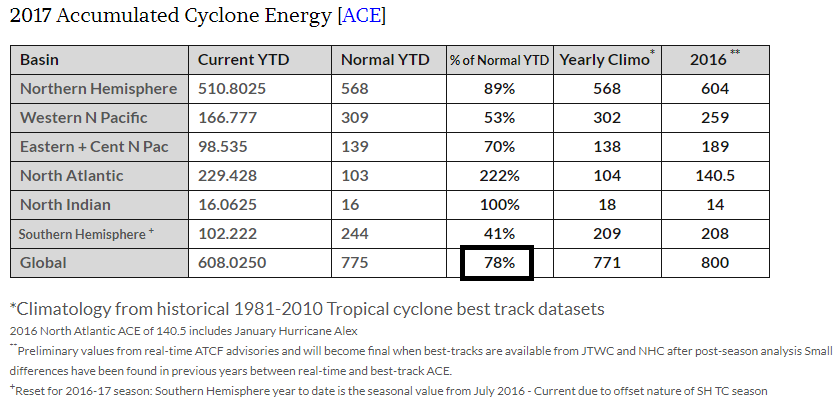

As we close out 2017, the ACE measure is 78% of normal across the globe; data courtesy Dr. Ryan Maue (http://wx.graphics/tropical/

Overview

While the Atlantic Basin experienced a very active tropical season in 2017, global activity was actually below-normal for the year by one type of measurement thanks to quiet seasons in the northern Pacific Ocean and throughout the Southern Hemisphere. The global “accumulated cyclone energy” as we close out the year is 78% of normal year-to-date and there are currently no named tropical storms around the world.

Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE)

One of the best ways to measure tropical activity is with “Accumulated Cyclone Energy” (ACE) which takes into account the number, strength and longevity of tropical systems. ACE is a commonly-used metric for assessing tropical activity because it is not dependent on exact numbers of named storms or hurricanes, but rather is based on both the intensity and longevity of all tropical storms and hurricanes (so a long-lived tropical storm could contribute as much ACE as a short-lived storm that reached hurricane intensity).

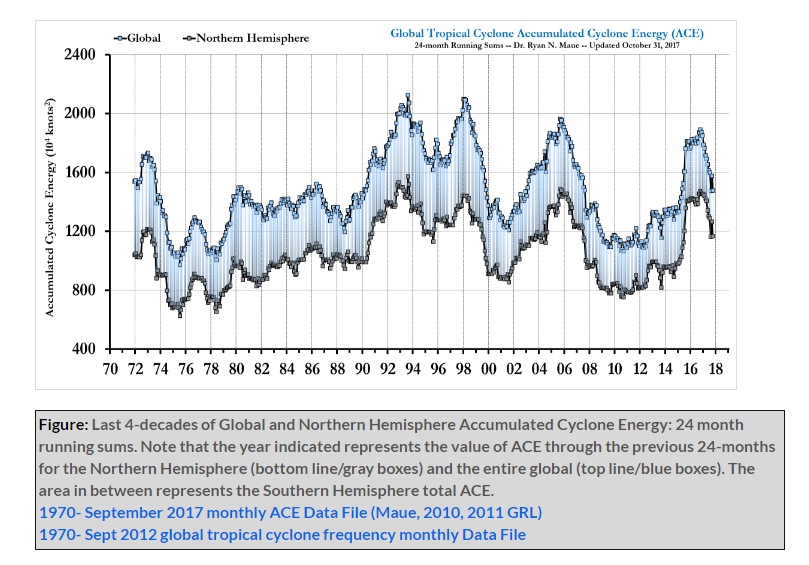

The ACE measurement from the early 1970's to the present with the most recent upticks associated with El Nino events in the tropical Pacific Ocean; data courtesy Dr. Ryan Maue (http://wx.graphics/tropical/)

The global ACE measure as we close out 2017 is 608.025 which is 78% of the normal year-to-date value and is lower than the level at this same time of year in 2016. While the 2017 ACE measure in the North Atlantic is more than double the normal year-to-date amount, it is significantly below-normal in the North Pacific Ocean and less than half of normal for the Southern Hemisphere.

The Atlantic Basin had a very active tropical season in 2017 with the highest total ACE measurement and the highest number of major hurricanes since 2005; map courtesy Unisys

Discussion

The 2017 Atlantic Basin tropical season featured 17 named storms with the highest number of major hurricanes (6) and highest total ACE since 2005. All ten of the season's hurricanes occurred in a row, the greatest number of consecutive hurricanes in the satellite era. The season began early with Tropical Storm Arlene forming during the latter part of April and didn’t end until early November with the demise of Tropical Storm Rina. The US hadn’t been struck by a major hurricane (i.e., category 3, 4 or 5) since Hurricane Wilma came ashore in southwestern Florida during October 2005, but Hurricane Harvey ended the record-length 4,323-day span in which no tropical cyclones made landfall in the US as major hurricanes. Over the past 48 years (1970-2017), the continental US has been hit by 5 category 4-5 hurricanes including Harvey and Irma of this year. Over the previous 48 years (1922-1969), the continental US was struck by 14 category 4-5 hurricanes. The latter stages of 2017 have been quite quiet around the world in terms of tropical activity with the global ACE measure from October 1st to mid-December tied with 2000 for the least on record for that particular time period (source Philp Klotzbach, Colorado State University).

One of the important factors that simultaneously contributed to suppressed tropical activity in the Pacific Ocean and increased activity in the Atlantic Basin was the formation of La Nina in the equatorial Pacific Ocean during the early part of the summer. Early in the year, most computer forecast models were predicting El Nino conditions in the tropical Pacific Ocean for the tropical season, but that all changed by the time the early summer rolled around. Cooler-than-normal sea surface temperatures in the equatorial Pacific Ocean (i.e., La Nina conditions) suppressed activity in nearby regions of the Pacific Ocean, but at the same time. helped to fuel tropical activity in the Atlantic Ocean as it reduced wind shear in that part of the world which, in turn, was favorable for unusually active tropical storm development and intensification.

Meteorologist Paul Dorian

Vencore, Inc.

vencoreweather.com